How To Become An Illustrator, Canto IV

Step Four. Promote.

Once you’ve got your portfolio together, you want people to see it—specifically people who can hire you.

Let’s make this an assault on multiple fronts. You young illustrators have many media available for self-promotion.

The world-wide web. Get yourself a website. It doesn’t need to be fancy, just a place to put up some samples of your work and your contact information. Nowadays everybody expects to be able to find you on the web, so make sure you’re there. Because we live in an age of technological marvels, you can build a website yourself, for free: http://www.moogo.com/. Here’s a review.

I’ve noticed illustrators have been posting their samples on flickr, which doesn’t cost you anything, either. Same with Facebook.

Print media. Even though I have a web presence, I rely on print media to let potential clients know I’m there. I strongly recommend that you consider a postcard mailing campaign. This will cost you a few skins, but I’ve found the return on investment to be worthwhile. I go to Modern Postcard to print my postcards. They’re in California and all they do is print postcards. A batch of 500 will set you back around $120.00. Once you go to their website, they really take care of you. There are downloadable templates so you may design your postcard to fit US postal requirements. You may submit everything to them electronically. They’ll turn your job around in less than 2 weeks.

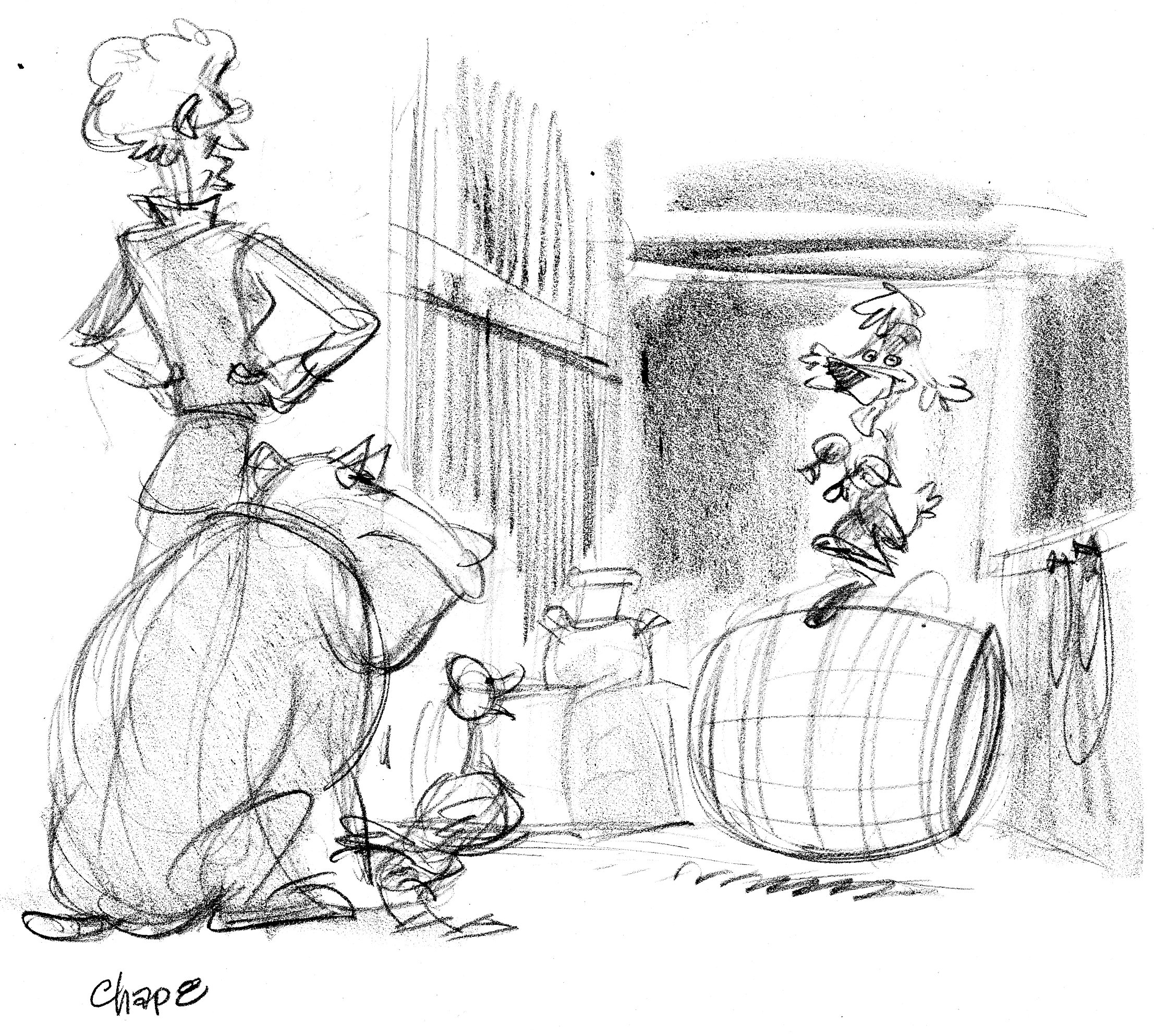

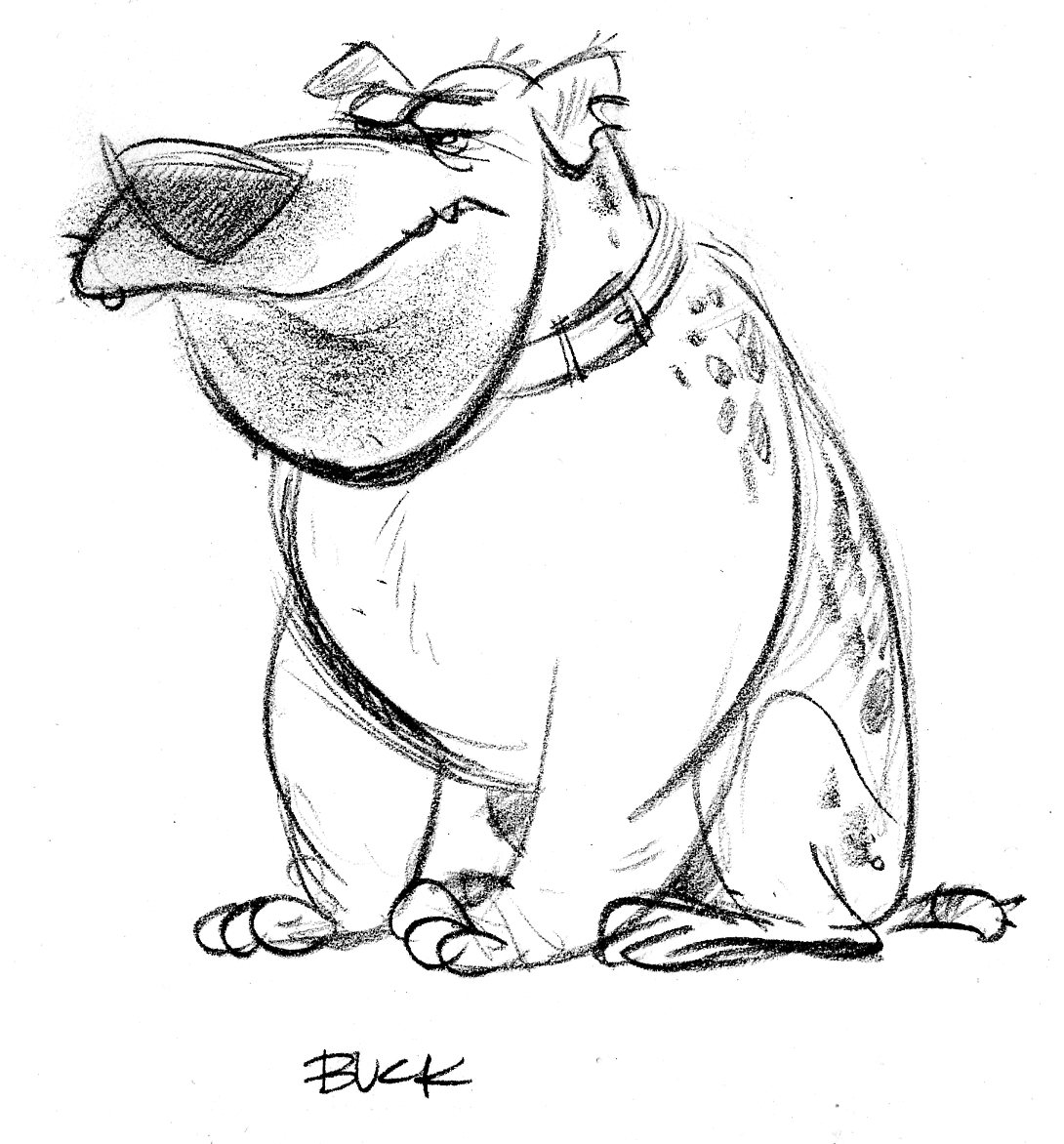

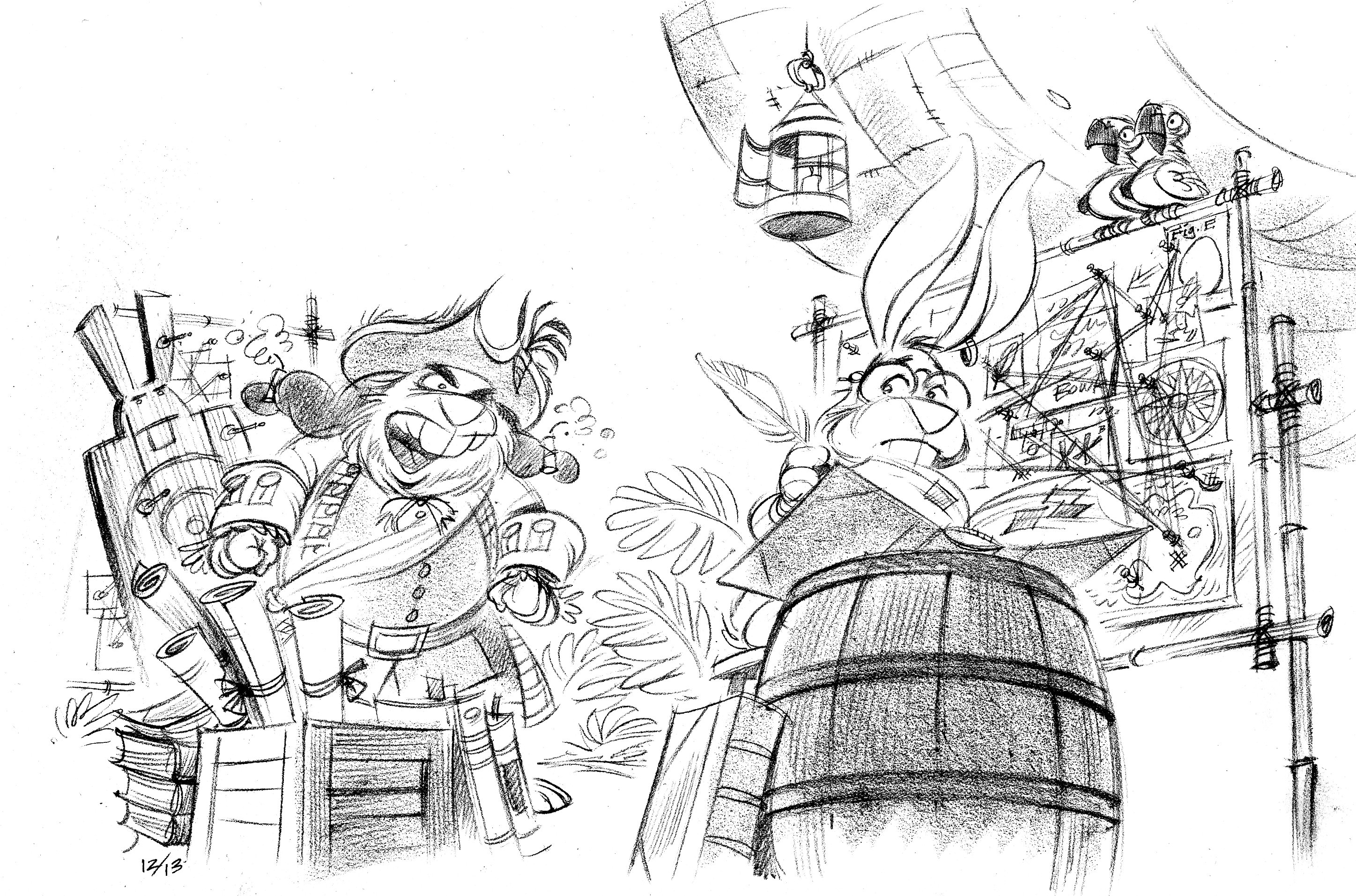

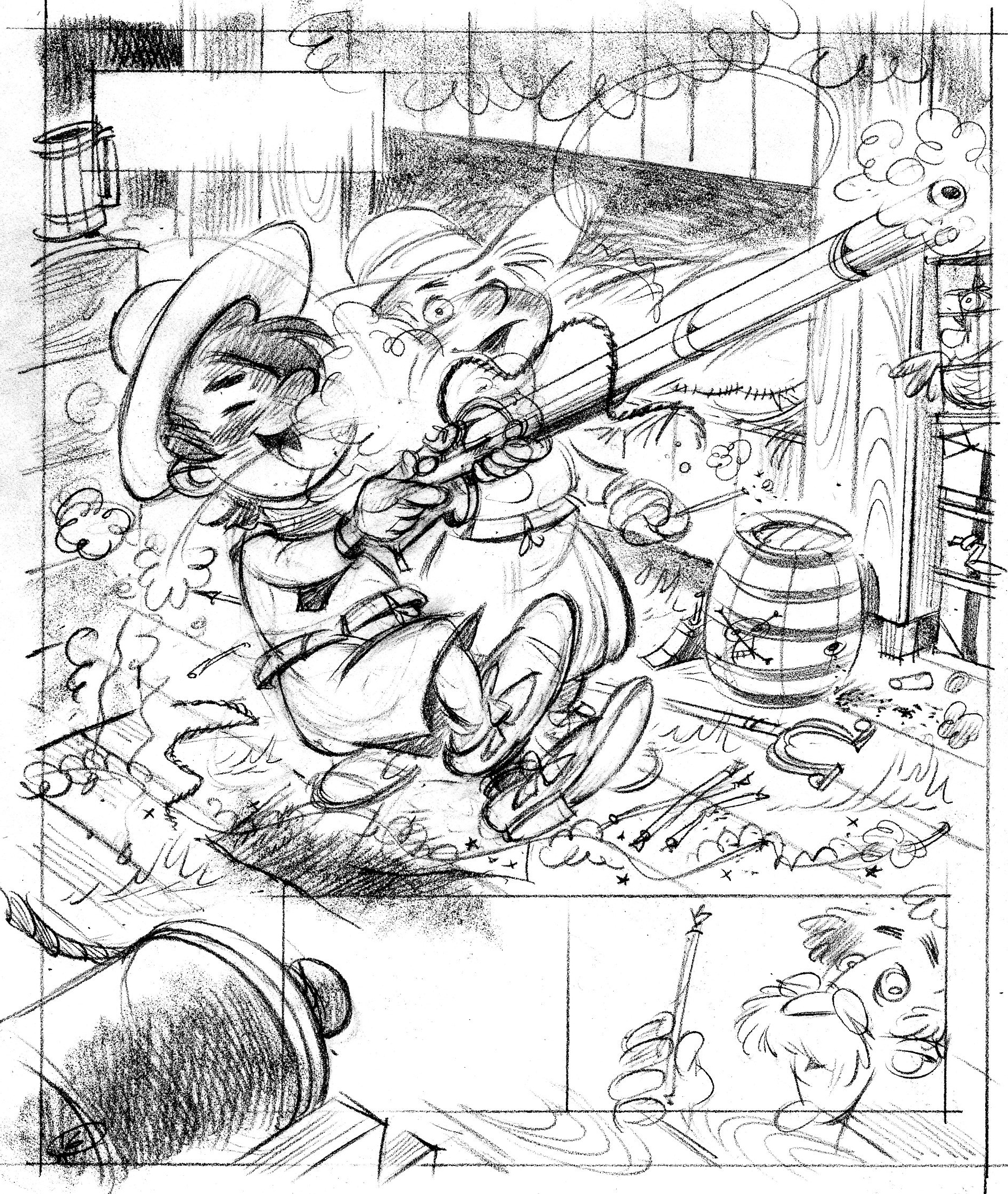

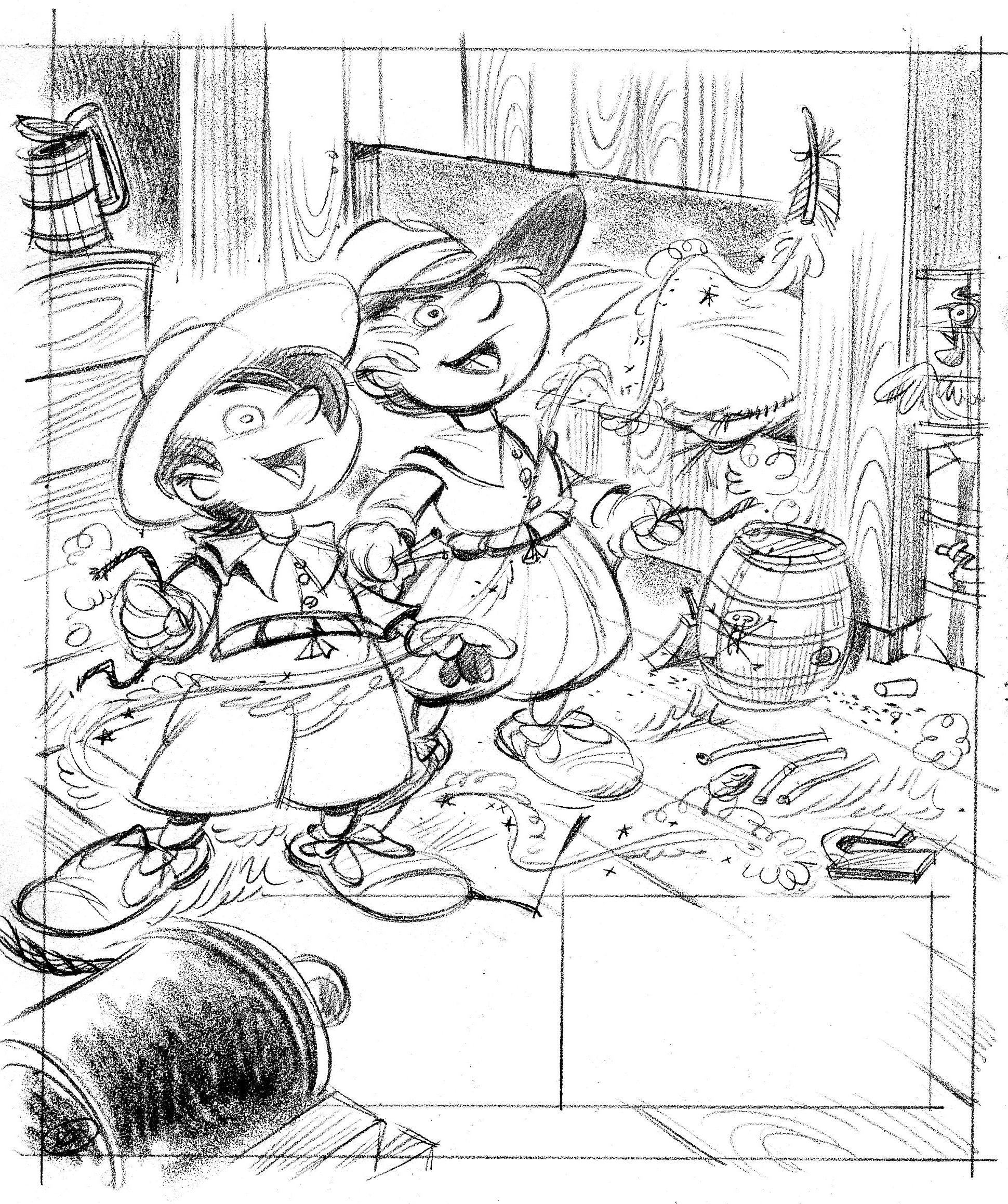

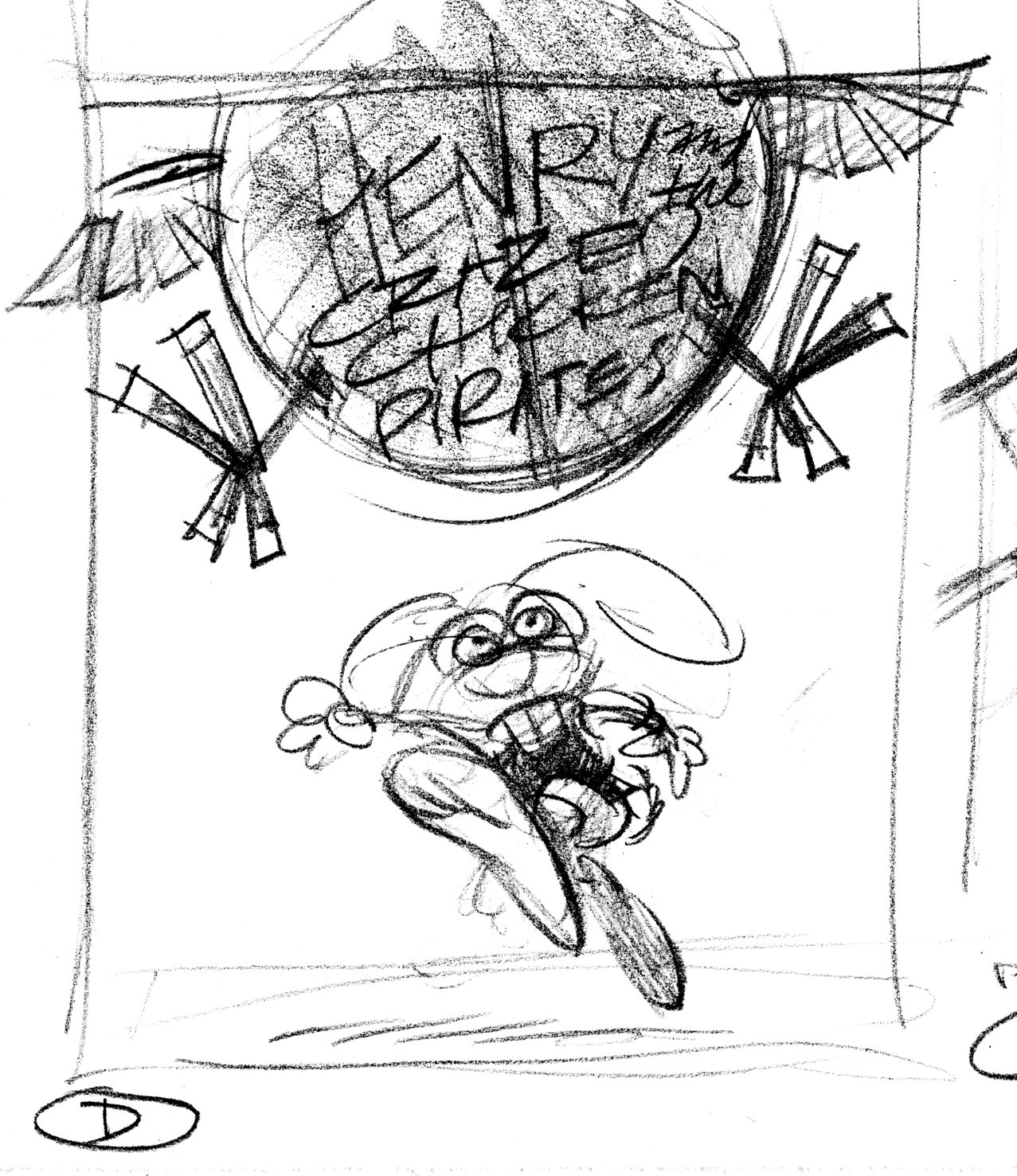

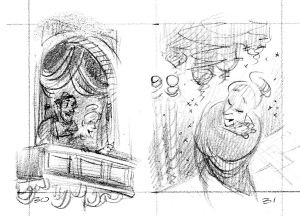

Put a show-stopping four-color image on the front of your postcard, and tell everyone how to find you on the back. If you can afford it, consider sending a series of postcards that tell a story. I did this and I got a great response from art directors—and a couple of jobs. I told a story in four images, and mailed my postcards every Monday for 4 weeks. By the time the fourth postcard was mailed, the ADs were waiting for it.

You’ll need a mailing list of people who might hire you. When I began, I wanted to break into children’s publishing, so I needed a list of art directors who work for children’s magazine and book publishers. I transcribed my list from Children’s Artists’ & Writers’ Market. If kids’ illustration isn’t your bag, a more general list can be gleaned from the 2009 Artist’s & Graphic Designer’s Market Of course you can buy mailing lists, but I prefer to build and maintain my own. Don’t forget to send a postcard to every member of your family and everyone you’ve ever met. You never know who may turn out to be an important contact.

Creative directories. These are catalogues of illustrators—you buy a page, put your images on it and the directory is sent out to zillions of art directors. This can get pricey. I stick with Picture Book only. I’ve tried some of the others, and I’d never been able to establish that I got a return on my investment; that is, the page didn’t generate more fees than I paid for it. Picture Book is a small slice of the illustration market—children’s only—which is the more effective way for me to promote myself.

Competitions. Don’t necessarily generate sales.

All your promotion should be run at a profit. If you spend a dollar on promotion and don’t get more than a dollar back, stop doing that kind of promotion and try something else.

Get this book and read it: Your Marketing Sucks.

DON’T e-mail art directors with unsolicited samples.